January Snow

We are getting whiplashed by sub-teen low temperatures and two feet of soft snow then temperatures above freezing and snow bombing everything as it falls out of the trees. Here is a little album.

We are getting whiplashed by sub-teen low temperatures and two feet of soft snow then temperatures above freezing and snow bombing everything as it falls out of the trees. Here is a little album.

Since I have been writing about microbial life in the soil for a couple of years now, I thought it was high time that I bear down on it and get a digital microscope. I was very excited to find one as a gift for my birthday but have to admit that setting it up was a little intimidating. So I put that off until recently.

I want to note here that you can expect a lot of trial and error when learning to take control of your own crop research. So far I have a lot of experience in the trial and error area. But that makes any success much more enjoyable. I am able to include a picture in this article because I ultimately was able to get the microscope going and capture a picture of some compost wildlife. There may be a lot more educational and entertainment value in the error part.

The manual directs that you use a specific kind of charger for a specific time to get the microscope going. Luckily I have lots of chargers lying around related to dead or defunct cell phones, flash lights etc. So not a problem yet. The next instruction is to turn on the microscope and then plug the USB connection into your computer. You also have to download some software that will display what the microscope sees. I managed to screw this up by not turning on the microscope before plugging it into the computer. If all else fails, read the instructions!

Once the device is plugged in, the computer scrambles to find a driver for it. This might take awhile. Don’t panic, take a break. Then you need to open the software. I did that and had a very clear live picture of my face. Evidently the software picks up the first camera it finds on the computer, in this case my external camera for Zoom meetings. Ok start over. I unplugged the Zoom camera. That worked and I could see fuzzy stuff. I figured out that on the computer there is no way to automatically zoom into focus. There is a dial on the microscope to do that – but then you are moving the microscope just a tiny bit. It turns out that a tiny bit is a big deal on a microscope. I gave up for the day and parked the software on my desktop.

For the next couple of days I scrambled looking for things to examine with the microscope. They included a blue opal, some cat hair and some holographic paper. Things were starting to be fun. I dug some compost out of the middle of the pile, which has a temperature of 43° even at 13° air temperature. Not much action there, so I left it to warm up.

The next day a breaker tripped and cut off all the power to the office. The computer seemed to recover, but the microscope would not work anymore. After trying several flying-by-the-seat-of-your-pants ideas, I dug deeper into why my computer was no longer talking to the microscope. I did mention that it is made in China. Evidently Windows doesn’t speak Chinese. It reported that it couldn’t find the software driver for the microscope. Then it offered to fix the problem. The problem started to get worse. I enabled “automatic updates”. They seemed to be stalled in the cloud somewhere. Windows identified “USB driver error (code 10)”.

I Googled “USB driver error (code 10)”. There was a solution that seemed to be free. I downloaded it and the program ran well. It identified hundreds of problems with my computer and offered to fix them. I clicked the button to do that and was transferred to a website where I needed to pay to fix the problems. Well okay, I had gone this far. $30 seemed like a small price to pay to fix hundreds of problems. I entered the key I had paid for and the program started to work. It hung up saying it couldn’t work while Windows was doing updates. Egad. Windows had finally started to do updates.

I closed the fix everything program and let the updates go on. They finished and said I needed to reboot the computer to finish the process. The computer shut down and started up again. But it didn’t make it. It offered to fix the startup problems and start. It didn’t make it again. I was getting desperate. I found an option to reset the computer to a previous version. Okay, it used to work right?

It churned for a while getting back to the previous version. I left to write Christmas cards. Somehow I was just not in the mood. I came back to the computer to see a message that it had failed to restore the previous version. I really don’t have much hair left on top or I would have pulled it out. I clicked a button marked “cancel” while trying to figure out who could repair this computer. Miraculously, the computer came back on looking and acting almost like it used to. I quit while I was ahead.

No one said citizen science would be easy. I started out today thinking that I might be able to see yeast in action. I have a winery after all. Back in the office I found a piece of wood I had brought in to test the wine was covered with ants. Trying to make the best of a bad situation I tried to get the ants under the microscope. Ants may look like they are moving slowly. Under a microscope they might as well be race cars. I couldn’t focus on them let alone take a picture. Back to the yeast. I got some really pretty pictures of yeast bubbles. The yeast itself seemed to be wavering but not clearly growing. Pretty wasn’t cutting it. Some stuff is just too small for this microscope.

As a last gasp, I put some now-warm compost under the scope. It looked like huge wet wood chips. Then I noticed something moving. I took a bunch of pictures mostly failing to get a clear image. It was a tiny bug like a beetle but white.

Thousands of different little creatures can live in compost. I tried a crazy search in Google, something like “tiny bugs in compost”. Amazingly it came up with ideas that included mites. I had never really seen a mite but it seemed likely. Soon I was looking at pages about oribatid mites. They look a lot like my compost bug and live mostly on the litter on a forest floor. There are over 12,000 kinds. Close enough!

So in Article 1 we learned that citizen science is not that easy; that you might find help on the Internet or not and that it’s really pretty cool if it finally works. Next month I’ll try to use my new digital PH meter. Wish me luck.

Farming and gardening have been key components of human life for thousands of years. They produce food but they also create a huge market for goods and services from companies aiming to farm the farmers. In taking on the production of food and maintaining the independence necessary to realize a profit, farmers often find themselves needing to invent their own equipment and do their own research.

Farming is not a “one size fits all” business. There are tremendous differences in soil and climate, crops and markets, often year to year. That opens up a lot of room for information sharing and “citizen science”. Those are the kinds of information I find most helpful as a farmer. In that vein I want to share a couple of inventions that I have developed for my farm and welcome any other ideas and experiences from other farmer/gardeners.

Usually coming up with something new requires a significant amount of trial and error, or as accountants like to call it “research and development”. In my case, after learning how important it is to give nutrients back to the soil in order to maintain a healthy biome, I tried different ways to mix mulches and spread them on the soil around my grape vines.

I thought I had the perfect combination in a very large old mortar mixer and a wheel barrow if I could make the loading simpler. So I built a nice concrete block stand for the 800 pound mixer so a wheel barrow could pull in below it and I built a platform next to it for easy loading. With everything in place I ran an electrical extension cord 300 feet out to the mixer. It barely turned, certainly not without enough strength to mix a hundred pounds of compost, manure, shredded prunings and biochar. So much for the perfect combination.

I looked into running heavy-duty wire out to the mixer. Very expensive and not guaranteed to work. I mixed everything by hand for a year or so. Hard and time-consuming. So one night I rethought the whole process. Despite its weight, the mixer only has a 20 to 30 gallon capacity. Everything would need to be put into buckets or larger containers, lifted onto the platform and dumped in the mixer while it was running. Then the load would need to be dumped into a wheel barrow and run out to where it was needed.

But what if I made something from a 55 gallon steel drum that could mix the mulch? 55 gallons would be a lot more efficient than 20 or 30. Actually, if I could roll the barrel, it would mix itself. If I could add ingredients from different piles right into the barrel in no particular order, no preloading would be necessary. The mulch-mixer-mover, (M3), idea was conceived.

Building it took part of a day. Used oil barrels cost $10 at Real Steel near Kettle Falls. Some steel pipe fittings and other odds and ends, mostly from around the shop, rounded out the materials needed. This article is probably not the place for technical details so I will skip those. The photo should help. In use, since the weight above and below the center axle is balanced, a 200 lb load can be pulled into place with one hand. After you remove the hatch and roll it over a few times, the load is dumped and ready to spread with a rake. Simple, fast and cheap.

Another continual chore around the garden and vineyards was sifting soil. I had some screens that I would put garden dirt on full of quack grass roots and use the screen to toss the dirt in the air, catch it again and sift out the roots. The same kind of cycle was necessary for refining compost, getting bark out of sawdust or tree roots out of dirt.

This was a case of reinventing the wheel. I thought of other devices I had seen for sifting gravel deposits and mining ore. They all used a rotating screen with a slight angle so fine material would sift out near the top and larger pieces would fall out of the back. This setup is called a trommel. I didn’t know that at the time but found a bunch of videos online on how to make your own “soil sifter”. They were all a little different and took some time, an electric motor and some other material to build. Or you could pay $500 for a really nice one from Europe. Since then with the word, trommel, I can Google hand crank versions for under $200.

I didn’t have much time or money but one day I was exasperated with a sore back. I knew I needed to upgrade from the handheld screen sifter. So I decided to just try out the concept. I started with a cylinder of 6” mesh screen that we had made into trellises for tomatoes. I put some finer 2” hardware cloth inside. Then I set it on top of a wheel barrow and tossed in a few shovelfuls of sawdust and bark. I rolled it over a couple times and voila! The bark stayed and the sawdust fell into the wheel barrow. I dumped the bark out the back. No need for motors or anything else. Now sifting soil is almost fun.

I would say these are the two biggest time and labor saving gizmos on the farm. There are a few more, but you get the idea. Work with what you have and spread the word. Nearly the same concept applies to doing your own tests on soil and plant vitality. A big new trend in crop management is to test the sap of both crops and weeds. The density and Ph of the sap can tell you a lot about what is going on with the plants. It changes daily, even hourly. You can quantify the effects of water, fertilizer, sprays and other management practices. More about that in another article, but for now, make your own gizmos and control your budget as well as your crops.

and other issues…

It was September 24th as near as I can tell when the Barreca Vineyards website crashed along with several others hosted by my friends Scott and Elaine at Secure Webs. An upgrade to their web management software nuked quite a few sites that I manage. Although I got them running again, I didn’t notice immediately that Scott had restored Barreca Vineyards from his company’s backup. That backup turned out to be from early July. It contained its own backup system which immediately overwrote all more recent backups which meant that before I could post anything new, I had to repost everything on the site added since July. I didn’t get around to doing that until today (November 11th).

With the Farmers Market, wine harvest and a lot of orders for Map Metrics, nothing changed on the site for 3 ½ months. The market and harvest have been finished for a couple of weeks and now I am finally cutting through the backlog to write another blog. Let’s just write it off as another supply chain problem.

So now it is pretty-much winter. The smoke is long gone. The drought is gone. The leaves on the trees are almost all gone. The “holidaze” are coming on. It’s high time to crank out a blog before it becomes time to write a Christmas newsletter.

In the “Under and Orange Sun” blog I show our neighbors’ cat, Pete, sleeping with my visiting daughter, Bina and grandkids. Earlier in the year we had a stray cat arrive who we called Spicy. She was loud and pushy but loved food and people – pretty much in that order. Also she got along with our dog, Gretchen. Our old cat, Gray-C, was not thrilled and dead set against Spicy or Pete entering the house. Pete is very much a scaredy cat when it comes to Gretchen or Spicy but not Gray-C. Those are the 3 cats in the problem. (In the physics world the “Three Body Problem” has to do with moving masses of gravity affecting each other and the chaotic mathematics that ensues if not given enough data. This was a little like that.)

We had a temporary fix when I put a cat door on the office. Spicy could get in. We fed her there and she seemed to love it. But she kept trying to get into the house. Gray-C was no match for her in size, but Gray-C can be very loud which brings people running to defend her and keep Spicy out of the house.

In the middle of the summer, friends came to the rescue by adopting Spicy, renaming her Cosmo (actually more fitting for her personality) and setting up food and shelter at their place several driving miles away from here. That allowed Pete to move into the office where he sleeps during the day and goes back to his real home at the neighbors for food during the night. He sometimes tries to get into the house but is easily discouraged.

This worked well until August 19th when the cat came back. It turns out that several miles by car is only about a mile as the cat goes through the woods. Cosmo (AKA Spicy) chased Pete out of the office and would have damaged him severely if I had not held Cosmo off with a hose while Pete scuttled back to the neighbors. We enticed Cosmo into the office with food and locked her there until her new “owners” could pick her up.

That worked for about another month until one morning I walked into the office to find Cosmo and not Pete. Since then I have driven Cosmo back “home” several times to the sound of loud complaints and a restless pacing around the car. She seems to feel good when released back home and has not shown up in this wet weather for awhile. But a surprise appearance and ensuing chaos seems to always lurk around the corner.

Since last writing any kind of blog, I have managed to get older. Daughter, April hosted a 74th birthday party at her house which was much appreciated. I was glad to see improvements around her place since she and Tony bought it this summer. Since then April also bought a used hybrid Toyota Rav4. I’m totally jealous but still unreasonably loyal to my own 21-year-old gas-powered Rav4. Birthday presents included a digital microscope. I am eager to use it but must confide that I have not found the time since September.

Time, a constant theme of this blog, has opened up a little since the farmers market ended the day before Halloween. Grape harvest and wine was still going on. The market was very good for us this year. We have some regular wine customers. We like our fellow marketers and the food they bring. The harvest went well basically but was a little smaller than I hoped. The extremely hot dry summer gave way to a wet fall making for a smaller crop that ripened late.

The hot weather built up demand for white wines. We are almost sold out of those. Meanwhile it made many of the red wines look to still be working since the wine expands when it is warm. The upshot is that there are almost 200 gallons of red wines ready to bottle. They go back to 2017. You could look at it as job security.

Not that I need more work. The map business was good. Fire fighters wanted maps. Even COVID inoculators wanted maps. Making maps is a good winter activity. Many of mine have not been updated for too long. (Did I mention the time crunch here?) So I did the obvious thing and got involved in another big project.

Actually I was volunteered for this project. Hudson’s Bay Fort Colvile (no it’s not Fort Colville) was founded in 1825. The bicentennial is coming up in 4 years. Most people would write this off as more “old stuff”. Maybe some of you have noticed that with all the conflicts of 2020 and 2021 a lot of history has been re-examined and brought back into the conversation about who we are and how we got to be this way.

The two most important salmon fishing locations on the Columbia River were Kettle Falls and Celilo Falls for thousands of years. Both are now submerged behind hydroelectric dams. As such, Kettle Falls was the annual summer gathering place for local Native American tribes from hundreds of miles around. Hudson’s Bay fur traders decided to capitalize on the location without really admitting that they were doing anything more than starting a farm. They established a fort charged with providing food for the whole network of trading posts west of the Rockies and loading boats with furs to take down the Columbia and bring back trade goods while getting a tremendous unacknowledged boost from the natives gathered at the falls.

They built the boats here too using the skills of Métis, mixed blood French and Indian voyagers, who designed and maintained the boats and paddled thousands of miles each year to sustain the fur trade. The fort, the characters and the colonization create a fascinating tapestry of intertwining stories. They are the cultural heritage of the peoples who have lived here the longest, most of whom have both Native and European ancestry.

To preserve the history and open the conversations around this event I have created a web site which keeps expanding with new discoveries and the legacies of people searching for their own history. It is time-consuming and sometimes exhausting work but perhaps the most important thing I do. Grapes and wine will come and go. Promoting Regenerative Agriculture, accurate maps, biochar and additive-free wine is important, fun and sometimes profitable. But in the longest run, bringing our local heritage to life again in the minds and activities of everyday people will affect generations to come.

So forgive me if communication has been a little slow. New challenges and crises, like cats, come up every day. There are plenty of good things to do and share. And I’m glad to be able to do and share them with so many good friends and family.

A while back we watched Shang-Chi, a Marvel Series blockbuster with lots of digital effects showing scenes set in Shanghai and a hidden village deep in a bamboo forest. Truthfully there was a lot of FX involved in the forest but they must have started with images of the real thing. The real thing showed acres of 100 foot high bamboo stalks so thick you could barely walk through them. In Shanghai there was a martial arts fight on bamboo scaffolding covering the side of a high-rise building. Clearly this was bamboo like I had never seen it before.

In my vineyard and those nearby we use bamboo as part of our trellises and for net-setting poles. It got me thinking about growing bamboo on the farm. What does it take to grow it? How does it affect the soil? What can it be used for? And just what is it?

Fundamentally, bamboo is grass, very big grass. I tend to think of grass as covering a prairie. Its large root mass in relation to its above-ground size gives it the ability to spring back after being eaten or mowed. Properly managed, it creates some of the most fertile farmland in the world. As pasture it gives us livestock and meat. As grain it gives us baked goods and sprouts. Do those attributes still apply to super-sized grass?

Not so much. There are close similarities. Bamboo comes in two basic types, clumping and running. Clumping is like the fescue in most lawns. It grows in bunches and spreads slowly. Running is like Spreading Brome, commonly referred to as Quack Grass. The biggest varieties of the over 1000 species of bamboo are clumping types that can reach 100 feet in height and 12 inches in diameter (Wikipedia). Like corn (also a grass), they need rich soil, warm temperatures and plenty of water. They don’t grow here. What we can grow are running types which are much more forgiving of temperature and soil types.

Therein lays a problem. Think Quack Grass on steroids. Running types are considered an invasive species. Some types of bamboo can grow 3 feet in 1 day. Their runners can go 20 or 30 feet underground. Once a stand is established, it is nearly impossible to eradicate with non-toxic means. I needed to talk to someone who actually grows bamboo. Fortunately my neighbor, Rufus Cabral is that someone.

We buy bamboo poles and stakes of different sizes from him on occasion. We don’t have to do that very often because bamboo lasts. In fact it is resistant to many things that wood is not. Deer and insect pests seldom bother it. If left above ground, sun and water in this dry climate have little effect. When it is a young sprout, most varieties are edible after boiling off the cyanogenic glycosides, mild toxins with a bitter taste. Stalks reach full height in the first year but take 4 or 5 more years to leaf out and harden. The mature stalk can live for 10 years or so. The leaves emerge in the spring and hang around until the next spring, then fall off as new leaves emerge. Like grass, the stalk (culm) has nodes, which can be cut to form cups or used as floats.

Finding bamboo fishing net floats on beaches in Alaska, was one of the things piqued Rufus’s interested in bamboo. It is only one of the hundreds of uses of bamboo itself. Bamboo can be used for food, medicine, livestock feed and many fiber uses such as paper, eating utensils and construction materials. Bridges, houses and furniture can all be made from bamboo. Rufus points out that the mature wood is 40% silicon. This makes it hard on saw blades. Carbide is recommended.

Bamboo is strange in other ways. It can bloom and have seeds, but only very infrequently, happening on all stands of a species at once which then all die. Since it regenerates quickly and enriches the soil while it rots underground, this is more of a survival tactic than a catastrophe. Rufus described how the roots, when they become blocked by dry hard clay, exude moisture to soften the clay so they can move through. Ironically, when used to stabilize erodible stream banks, a common use, they can’t cross under the stream itself. He grows a variety found at the 10,000 ft elevation in the Himalayas and several others. But common types know as “fishing pole” and “yellow grove” died here.

The Cabrals got starts from a nursery on the East Coast. Trying to get new starts transplanted into pots that can survive the winter has been more challenging. One of the biggest issues, the expanding nature of running bamboo, has not been a big problem. The new sprouts are big and obvious, so it is easy to mow them down and contain the bamboo patch.

As for bamboo being good for the soil, maybe it is. The mulch of the leaves and density of the root system may fertilize the soil. But since the groves are so thick and persistent, nothing much but bamboo grows in the center of the groves and only grass near the edges. Essentially, if you have a steady use for bamboo poles or use it as food or feed, it is a dependable crop. It also makes good wind breaks and stabilizes erodible soil. But if you change your mind about that, it can become a big problem.

Bottom line: consider your options carefully. You don’t want to make a bamboo-boo.

It’s September while I’m writing this. It’s raining pine needles. After a stressful summer for most plants, you can see pine trees with lots of brown needles ready to drop. Ironically, you can also see grasses that have suddenly become green again after some heavy rain. Mother nature is preparing for winter. A good question might be “What is she up to and why?” A reasonable (even if highly irritating) answer would be “It depends.”

Along the lines of “The more you know, the more you realize that you don’t know,” a word of caution here. The differences in soils between sand, clay, rock and loam; the differences in crops between perennial, annual, orchard, field and row crops; the differences in weather between wet, dry, cold and hot; and the differences in terroir between hills, meadows, forest, minerals and microclimates are all important in deciding how to prepare your ground for winter. Things I write or you read elsewhere have to be interpreted by your own developing sense of soil.

Having said that, a good general principle is that nature avoids bare soil. So if you are thinking “Let’s get all of these stems and weeds out and leave a clean bed for spring,” please stop. Multiple bad things happen when soil is bare. Rain and snow make heavier pieces of rock and sand sink and lighter dust and clay stay in the liquid. When that dries, the clay layer makes water run off without sinking in. The water goes on to create erosion. The microbes in the soil die of thirst. Living plants, dead plants, mulch… anything is better than bare soil, especially if that soil has a lot of clay.

Your underground livestock: bacteria, fungi, protists, nematodes and worms need air, moisture, food and shelter to survive the winter. Living plants are the best because fungi exchange nutrients with plant roots in exchange for sugars produced by plant leaves. Fungi can also live on just woody material like straw, sawdust, cardboard and wood chips. That slows way down under a cover of snow and ice. But even plants that die during the winter are good food for the other organisms. Take forage radishes, AKA tillage radishes, for instance. In hard soil and clay they tunnel down several inches. When they die, they leave passageways for water to seep in stopping runoff and food for microbes and fungi.

My soil is sandy. When we got here we never found rocks in post holes, but also no worms. Red wiggler worms burrow down several inches to survive the cold. But they don’t like sand. They like warm rotting stuff and give your whole biome a big boost. I am building up my soil year by year, but for worm insurance I am also building up a large compost pile. The worms will migrate to the bottom when it gets cold and survive. They also don’t like it too hot. Right now it is over 90° at the bottom of the pile, too hot for worms. Up a little higher it is 70° to 80° and has a lot of rotting produce, worm heaven.

Out in the vineyard there is a nice crop of green grass. Soon the grape leaves will fall on top of the grass. This is the natural mulch that makes deciduous forest soil so rich and is built up just before winter. Unlike a garden or flower bed, the vineyard is a perennial forest of vines and pasture. Some people would like to have all the dirt around the vines tilled up. That would disturb overwintering pests like leafhoppers and eliminate weeds that would “compete” with the vines for nutrients. I don’t look at it that way.

Green plants, especially grass, feed fungi during the winter with sugars in exchange for water and minerals. The more microbes you have living in the soil, the more nutrients are available in the spring. The nitrogen in green grass is especially valuable. I intend to mow the grass before adding mulch, such as woody material or sawdust, over it. The grass will help break down the mulch layer. The best thing would be to have animals eat the grass and return it as manure to the soil. I don’t have the right critters for that and am pretty sure most of them would prefer the grapes to the grass.

Part of the deal is that grass has huge roots. I have potted grape plants outside and grass sometimes gets in the pots. Most weeds pull out of the pot easily leaving just the grape plant in the soil. Not grass. Grass wants to take all the soil with it when you pull it. It thrives after being eaten down once and bounces back. The big roots prevent grass from being pulled by grazing animals and give it a food reserve to draw on for the rebound.

The grasses on the Great Plains built fertility for thousands of years before being plowed under. At first the rotting grass roots were very fertile and crops were great. But after having all the organic matter removed each year and laying fallow over the winters, they have lost 70% of the carbon and 70% of their water holding potential (For the Love of Soil, Nicole Masters). So I want to keep the grasses in my vineyard.

In Frank Herbert’s book, Dune, giant sandworms produce a drug called “melange” (known colloquially as “the spice”), which is highly prized across the universe for its medicinal and mystical properties. (wikipedia.org) Although wildly fictional, some truths linger in that account. Melange is created when excretions of the sandworms’ larvae react with water and sunlight. At this point the tale gets a bit, shall we say, “messy”. In the real world, worm excretions, castings, are an indication of healthy soil and contribute to it. Can they eat sand? How big do they get? What is really going on down there?

These persistent questions kept making me think of someone one of my grape plant customers mentioned, “Marvin the Worm Guy” in Spokane. So I Googled it. Well the closest thing is Marle Worm Growers in Otis Orchards. As it turns out, the worm guy is Jeff Wood, who runs Marle Worm Growers, and indeed knows a lot about worms. I finally got a chance to meet him in person and we talked and walked around his place for a couple of hours. It could have been much longer. Jeff does educational presentations for Spokane Community College, Master Composters and Master Gardeners. He looks at worms as not just a commodity he grows and sells, but as a highly valuable component of healthy soil. Building healthy soil is his passion.

Jeff called microbes “engines of the soil”. Carrying that analogy a little further, worms are trains full of microbes spreading them everywhere they go. Worm castings are not just good plant food, they are highly refined and PH-balanced food that has some surprising qualities. Seeds drenched in tea from worm castings produce long healthy roots even before emerging from the ground. In a recent episode of the Regenerative Agriculture Podcast, Nicole Masters describes this effect as the highest yield per cost of any enriching application you can do to a crop, costing mere pennies per acre.

It is not surprising then that Jeff makes several kinds of compost tea and says that using compost tea on your plants is a technique that everyone can afford and is tremendously beneficial. He has a large tea brewer that preheats water, introduces air and grows microbes essentially overnight. So yes, he sells compost tea as well as a huge inventory of other products, besides worms, that are good for the soil. He also sells soil itself to landscapers, gardeners, greenhouses and farmers. He points out that crucial consideration are how much time you have and the nutritional needs of plants which change through the course of a season.

Foliar applications of tea enhance growth and can also control insects. They last 3 to 5 days and need to be modified and applied frequently. A root drench tea will last 7 to 10 days. Worm castings added to the soil last a couple of weeks and granular fertilizers, which Jeff also sells, can last a whole month. Every step of the way means more cost but more time to work with.

When they are young, plants might need some insect protection, mild nitrogen fertilizer and some soluble seaweed extract for its mix of minerals. With more growth in the middle of the season, plants can feed on more nitrogen-rich fertilizer like aged manures and of course worm castings as the plants put out green leaves. Toward the end of the season, plants don’t need as much feed but you want them to settle into the winter with organic matter that is composting and retaining moisture.

Through all of this, worms have their cycles too. Being so closely aligned with composting, worms like what compost likes: temperatures from 55° to 77°. Temperatures above 90° will kill them. At temperatures under 55° they are not very active. I asked about compost piles that can get to 160° F. Jeff told me that the worms will move away from the hot compost, usually to the bottom of the pile. When the compost is cooler but still gooey, they come back to eat.

Worms don’t have teeth. Like chickens, they grind up their food in a gizzard. So a little dirt or light sand can help break down the rotten vegetables and fruit (as long as it is not acidic like citrus) that is their main diet. If you are growing them in a worm bin, it is harder for them to get away from hot compost, so Jeff just adds a little vegetable matter in spots near the top of the bin. It takes 3 to 4 days for worms to eat a feeding. They eat their weight in food every day. If it takes longer, you may be feeding them too much. They like a combination of green (vegetables, grass and leaves) and brown food (wet bedding and rotten fruit) , with an emphasis on the green.

Marle Worm Growers sells a variety of worm growing equipment. A common thread is that worms move on to new food when the old is exhausted. So some systems have you add another box of bedding and food on top of the old, the worms move into the new food after a few days and you can remove the old box to get the castings. Similarly, some systems have two sides with a screen between them. Feed on one side and the worms move there. You can encourage the move by letting light shine on the old side and exposing it to a breeze. Worms hate that. Remove the castings from the first side and it is ready for new food. Keep in mind that the bedding, which can be shredded black and white newspaper, cardboard, peat moss or decomposing leaves in any combination is also consumed. Keep it as wet as a damp sponge but not too wet. Worms need air as do compost and roots.

This does sound a little complicated and there is even more equipment in Jeff’s operation to separate worms, castings and unused material. For small scale growers Jeff is a big proponent of systems that integrate the worms with growing plants. The most straight forward is a “worm tube”, basically a 6” or so plastic pipe perforated with ½” holes that the worms can crawl through. Place it straight down in a raised bed or vegetable garden with a fly-proof screen that you can take off to add ground up kitchen waste. Don’t add meat or oils, they smell and attract pests. The worms do the work of composting the food waste and transporting it to the roots of the plants for 4 to 5 feet around the tube.

Taking it one step further, there are “garden towers”. These are essentially worm tubes in the center of a 4 foot high structure that lets plants poke out the sides and feed off the worm castings carried out of the tube by worms. Additionally, you can pull the worm castings from the bottom of the tower and put them back in on top of the soil. This is great for gardening on your patio or porch.

What I have however is a vineyard with sandy soil. I learned from Jeff that the red wiggler worms are going to avoid the sandy soil. They want several inches of organic material on top of the sand. They will however bury themselves deep in the ground during the winter to avoid freezing. Even deeper, 3 to 5 feet, are nightcrawlers. They also produce castings from compost. Their deep holes help aerate the soil. They make great fish bait, but are harder to propagate.

There is a lot more to worms than meets the eye. The cast of worm species goes on and on. I am tuning up my compost pile to feed the red wiggler worms. I’m also covering it to keep in moisture and encourage worms to get closer to the surface. I noticed after uncovering it once that robins were right there pulling out some worms for themselves. You might want some worms for yourself. Feed them and they will help feed you.

When I was younger, not very studious and there was no Internet, I decided to add pigs to our menagerie of goats, chickens and a donkey. We had extra milk from the goats and I could supplement the pig diet with culled potatoes from the Doukhobors in Grand Forks, British Columbia. The pigs didn’t put on a lot of weight during the winter because they didn’t have much shelter, just some bales of hay. Realizing that was a problem, I built them a solar-heated pig house.

Actually that worked well and they loved it. Here’s the thing, pigs are naturally happy. They love to dig for food. Well they love food period, hence their reputation. You can’t really herd them, but you can lead them around with a bucket of anything tempting. They are smart and not really that dirty. They only pooped in one corner of their pen. Still they do get big, too big to wrestle or do much with. So eventually we gave our big sow to a neighbor and she didn’t last long there. Too much trouble I guess.

That was a different time and place. I didn’t get into the craze of pot-bellied pigs as pets which followed by a few years. At least it recognized the Marvelous Pigness of Pigs, which is the title of a book by Joel Salatin. Joel uses pigs as a study in the divine nature of nature. I would have preferred a little more direct description of pig farming. Salatin used them to transform a run-down family farm into a thriving regenerative food source by letting them graze on acorns in the woods.

Thinking back on my experience, I realize that I could have used them to plow and fertilize patches of ground for a garden. The old Case 22 bulldozer with a hand-cranked starter that I bought was lousy for plowing and hard to start. I would have had happier pigs and more pork. Common practices in raising pigs had skewed my understanding away from their real nature.

So it was with some surprise and enjoyment that I recently saw an email from Eileen of Ramstead Ranch near Ione discussing their use of pigs to prevent forest fires. No. We are not talking about Smokey the Pig. But remember those fire lines that fire fighters dig around a wildfire to contain it? Pigs do pretty much the same thing naturally but over a wide area and they love doing it.

So naturally this left a lot more questions in my mind and I arranged to talk to Eileen about them. Remembering how hard it was to keep these four-footed track hoes from digging under fences I asked how Ramstead kept them in. Eileen said it’s no big deal once they become familiar with electric fencing. At Ramstead they start them young getting to recognize electric fence wire. Being pretty smart they tend to stay clear even if it is not turned on. So a little electric fencing that can be moved to rotate pasture areas is all you need.

They do well on grasses and friends of ours have used them to root out quack grass, which has LOTS of long-running roots. But bushes and their roots, thistles and a wide variety of plants are all dinner for the pigs. At Ramstead they can use a one-two punch by having cattle trample bigger woody material and pigs rotovate it into the ground. After a season or two of this kind of rotated grazing, their brushy woods with lots of “ladder fuels” (small trees, brush and low branches that fire can climb up into tree tops), are eliminated and the woodlot turns into “silvopasture”, grasses under trees where cattle, sheep and pigs can graze comfortably away from scorching sun.

Don’t get the idea that these are far-flung fields where wolves and dogs can become a problem. Pigs still need fresh water and supplemental feed that need to be hauled out to them. If they are close to where they were raised as young with plenty of food and drink, they are more likely to stay close even if they escape the electric fencing.

So remember what I said about pigs being naturally happy? I’ve heard stories of them digging head first up to their hind legs in pursuit of tasty roots and then popping back up again ready to dig out another. But normally we think of them in crowded pens, making a mess, smelling bad and creating huge runoff problems for streams and neighbors. Salatin notes that “Factory farming pigs makes them stressed, so they fight each other and develop other problems.” He decries efforts to find a “porcine stress gene” and genetically modify it as if that would eliminate those problems.

Eileen is proud of how low-stress life is for Ramstead’s pigs. She notes “Our pigs live outdoors in the sun and shade. They run, root, wallow, lounge and get to behave like real pigs.” The waste they produce is worked directly into the ground where it does the most good. As a result the meat is cleaner, leaner and tastier than factory-farmed pork. That is the kind of benefit from recognizing the marvelous pigness of pigs that I didn’t realize when we had them.

Actually I’m also recognizing the difference between how a city boy (that would be me 40 years ago) sees animals as cows, horses, chickens, sheep and pigs but a country boy (not that I am entirely there yet) sees breeds of cows, horses, sheep and pigs. Beyond that if you really raise these animals, you see personalities. There may be general tendencies of breeds but for instance can you really say that since you have known one cat, you know them all? Both nature and nurture make a big difference.

Eileen prefers Berkshire pigs, a heritage breed recognized as far back as 1642 in Reading England as renowned for its size and the quality of its bacon and ham. They are also known to be gentle and friendly to other animals and people. So pigs just want to have fun. Let them be themselves and we will all be happier and safer.

Under an orange sun the sky is gray and the shadows are blue. With temperatures above 100° for many days in the last month and the air quality often in the unhealthy range, today (August 8th) is very rare since it has been raining since early morning. At first smelling like wet smoke, it is now cool and humid enough that you can see your breath at 60°. We can add that to the long list of strange changes this summer.

There may no longer be any such thing as a “normal” day, but our habits have definitely changed. Those precious hours when there is morning light and cool air, prompt us to rise at 5:30 am or earlier and work outside for hours before making breakfast. Often we nap in the afternoon and go to sleep at dusk when the outside temperature finally slips back below the 75° indoor temperatures and we open the house and office to cool them down.

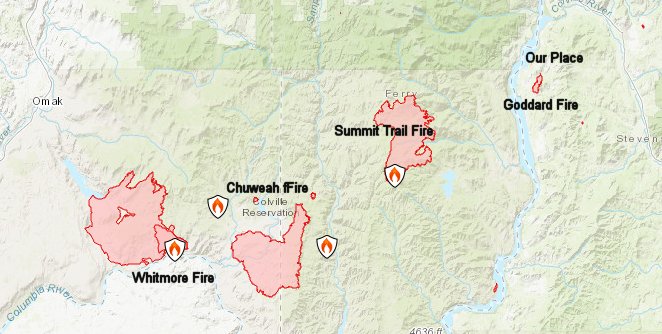

Then there are the fires. The Chuweah Creek Fire near Nespelem is 50 miles away (95% contained), but we are directly downwind. It started on July 12th and is now 36,752 acres. Another fire, the Summit Trail fire, started in the same lightning storm and is now over 28,000 acres (30% contained), just to the southwest of that is the newer Whitmore Fire. that is at 55,970 acres (20% contained) started from a thunderstorm on August 3rd. We are directly downwind of all three of these fires most of the time.

Not to be outdone, we had our own local fire, the Goddard Road Fire, now at 800 acres but contained. Contained fires still burn. None are considered out until winter, although this rain really helps. It was July 16th. We had already purchased more fire extinguishers and a backup generator. In the morning I picked pie cherries and made a pie. That afternoon I had planned to mail rock club newsletters in Kettle Falls and go on to Colville. (From my journal.) “I was pulling out of the driveway after a vehicle had gone by with the siren wailing. Then a plane went in the same direction. I had a bad feeling about that. As I drove to Kettle Falls to mail the newsletter more and more emergency vehicles passed me going south. I knew there was a new fire and it was close by. On the way, (our neighbor) Vern texted a picture of the plume and Cheryl texted that the fire was 50 acres. I had intended to go on to Colville but scratched that, picked up some water, mailed the newsletters and headed home”

Thus began a long night of preparing for level 2 evacuation (be ready to leave at any minute). We were packing clothes, valuables, important papers, photos and other memorabilia. We were on the shortest route to Lake Roosevelt from the fire. Soon a line of six Fire Boss airplanes was flying over us one after another dropping 800 gallons each of water on the fire. They were joined by helicopters of different kinds sucking up water or lifting it in buckets. A huge red jet followed to dump fire retardant on houses, some owned by friends of ours. A spotter plane flew in circles higher up running the show. After dark they went home. We stayed home, alert for the smell of smoke. So much for going to the Farmers Market in the morning.

Two days later my daughter, Bina, and her children, Ovid and Nala came to visit. The evacuation warning had been lifted but it came back on because the Goddard Road fire flared up again. So they got to see the air show for themselves. They also were put to work around the farm. Ovid used the battery-powered trimmer in the vineyard. The whole family helped unload wine bottles and break down cardboard boxes. Then Ovid and Nala came with me to drop the cardboard at the recycling center, talk to the Real Steel junk yard people about our Subaru body and get a load of sawdust dumped into the pickup at Webley Lumber. And oh yes, they went swimming at nearby Bradbury Beach on Lake Roosevelt every day.

We also had another visitor, our neighbor’s cat, Pete, who evidently loves kids. He slept with them in the back of their pickup truck.

Other critters added to the cats. A large gopher snake fascinated Gray-C but left with no harm to either. Gray-C did surprise us with a dead weasel. A small frog decided that the spout of our watering can was its favorite place and returned there day after day even though he was washed out each time I watered the grape cuttings. Maybe the strangest critters were not here but were spotted by Forest Service rangers travelling with Chris Wujek, who I wrote about last year, camping in the Kettle Range. Son-in-law, Tony Houston, sent pictures of the camels and the rest of the herd, less one goat, that the herders were roasting for dinner over an illegal fire, which caught the attention of the Forest Service Rangers.

Despite the drought, summer brought a bounty of fruit, which also kept us busy; drying cherries; making pies; freezing strawberries, blue berries and apricots; spreading peaches and other fruit on corn fritters and looking mostly “fruitlessly” for huckleberries. The few that survived were shriveled and small. The forest roads were empty and lined with dried up bushes and trees. The irrigated grape plants like the sun and are growing a large crop if it survives the bugs, the birds and the intense heat. The young plants in pots have been gathered under our big filbert tree for shade.

The fires spurred an uptick in map sales. But washing fire fighters clothes has been taking up the morning hours of the local laundromat. We wear masks for ash and smoke some days as well as for Covid 19 on others. On the evening of August 3rd and 4th, thunderstorms crashed around us all night. Thankfully, they brought a lot of rain and very few new fires. We didn’t get much sleep but will trade sleep for rain any time.