Past Lives of Concrete

Ever since the 7.8 magnitude earthquake in Turkey and Syria on February 6th we have seen a lot of pictures of collapsed concrete buildings. You might get the idea that concrete is a heavy and dangerous building material that it would be wise to avoid. That is much more easily said than done. Every year, 30 billion tons of concrete are used globally (Northwestern University). That’s almost 4 tons for every person on Earth. Concrete accounts for 8% of worldwide carbon pollution (Nature, The international journal of science), a carbon footprint larger than any single country other than the US or China (The Guardian). The reason that the impact is so big is not just that we use so much of it but also because of what it is and how it is made. But before we get into that, another question might be “What has this got to do with the North Columbia, where and how we live?”

When you travel north from Kettle Falls to Northport along Highway 25 or more historically, the railroad along the highway, you pass large limestone quarries on both sides of the river. Limestone is the critical main ingredient of concrete. Many of those quarries were used to create Grand Coulee Dam. You can still see concrete silos near Evans where cement was stored and then shipped by rail to the dam site. The Panorama Gem and Mineral Club still collects calcite crystals from these quarries.

Limestone (CaCO3) is a sedimentary rock that formed millions of years ago as the result of the accumulation of shell, coral, algal, and other ocean debris. So those white and gray rock cliffs along the Columbia were once living organisms. Lime, or calcium oxide (CaO), is derived from high quality natural deposits of limestone and is the main active ingredient in cement. Lime is left when the carbon in the limestone is driven off by heating it to 1400º C (Nature). The heat for the process building Grand Coulee was created in wood furnaces. The wood came from the local forests, often those once covering the limestone quarries. The process released both carbon from burning the wood and carbon from the rock. (More modern kilns use coal and gas, fossil fuels). A lot of carbon is in that rock.

Limestone-based cement and mortar have been around well over the 2000 years. The most long-lived and famous structures were created by the Romans. The key to Roman cement’s longevity appears to be the use of volcanic ash, or pozzolana. Where modern concrete is a mix of lime-based cement, water, sand and an aggregate such as gravel, the recipe for concrete set down by architect Vitruvius in the first century BC involved pozzolana and chunks of volcanic rock, known as tuff. When it comes to Roman marine concrete, used to construct piers and breakwaters, research published in 2017 found that the addition of sea water actually strengthened these structures over time, making them harder and harder over the millennia.

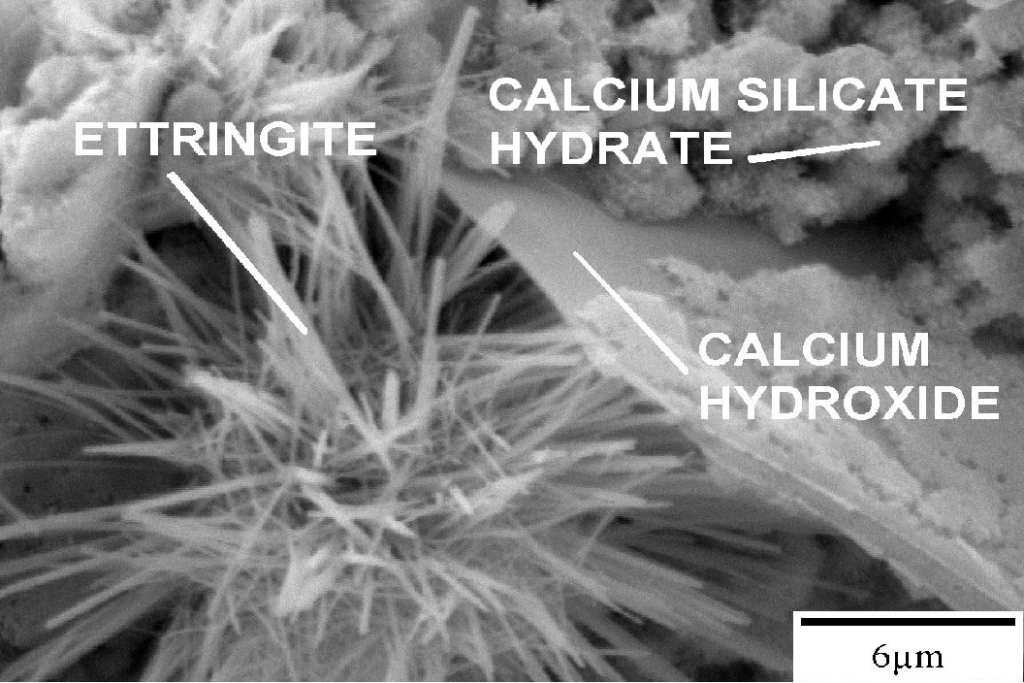

In Northeast Washington we find ourselves in a concrete paradise. With volcanic ash from Mt. St. Helens and volcanic rock from the Columbia Basin, we could make some very long lasting cement. Concrete is bound together when cement powder is mixed with water and creates crystals. Yes, those same calcite crystals found in our local quarries are what binds to the mixture of sand, small and larger rocks that becomes concrete. If you examine concrete under a microscope, you can see those crystals.

Of course, there is a lot more to making good long-lasting concrete. A big breakthrough was to embed metal into concrete. (Full disclosure) I live in an underground house made with 56 yards of concrete spread over 3 miles of rebar and buried under a million pounds of earth. This has proven to be a structure that is very resilient to heat and cold. It basically absorbs the average temperature of the earth (50ºF) and will not freeze in winter or get very hot in the summer. It could be absolutely air tight but that would be dangerous, so it is not. It should hold up for the next 300 years or so.

In the long term, the problem is the rebar. Water and corrosive chemicals, many of them natural acids, can eventually seep in through spaces between the Calcite and Ettringite (C6AS3H32) crystals and corrode the iron rebar. A few years ago, I had a pad poured from Colville Concrete that was reinforced with fiberglass, basically Silicon Oxide the main component of sand. It does not corrode. (I might not have needed the rebar.)

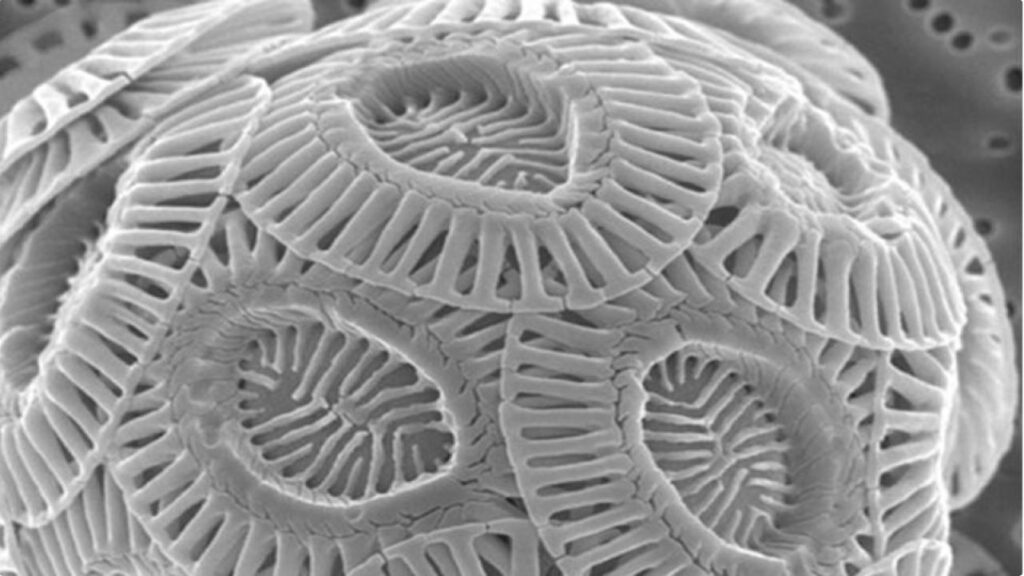

As you might guess, with the huge economic value of concrete ($330 billion US and growing, worldcement.com) and the corresponding huge carbon contribution to climate change, there is a lot of work being done to minimize the carbon footprint and maximize the strength of concrete so less is needed. Some of the approaches include recapturing the carbon driven off by heating in kilns and turning it back into methane fuel or blending it back into the concrete; using bio-derived fuels in concrete kilns; adding chemicals to make stronger concrete with less cement; adding biochar to cement; building with laminated wood like that created by Vaagen Lumber; and using biological processes such as those in coral to cement rocks together. My favorite approach so far is farming Coccolithophore Microalgae. This is one of the organisms that limestone is made of. A team of researchers at the University of Colorado Boulder has implemented This approach. According to the team’s estimates, only 1 to 2 million acres of open ponds would be required to produce all of the cement that the U.S. needs—only 1% of the land used to grow corn. (Technology Networks) Technically, I could grow my own cement. Farm On!

After this article was written for the North Columbia Monthly I had a conversation with Hayden Binde from Biosqueeze. Their core business is using a micro-organism-infused liquid to seal methane-leaking oil wells. But that same infusion can bond soil to make it stronger than concrete using safe biology that actually sequesters carbon. Along with at least one other company they are researching development of the process to make carbon-negative building materials.